Escoles dataficades sense control

15/11/2022

Every day there are an increasing number of warnings about the harmful effects that too much screen time can cause. This is not simply due to overstimulation, the content viewed, concentration problems or lack of sleep; rather, what is of particular concern is the potential – as of yet unknown – impact on the character and psychosocial development of children. Despite this, children in Catalonia (5-11 years) spend almost the same time online as they do at school, a statistic that is extreme for anyone with knowledge on the issue. To address this problem, parents have tools that allow them to limit and control what they are doing when browsing at home, but are they aware of what happens when they go online at school?

Children in Catalonia (5-11 years) spend almost the same time online as they do at school.

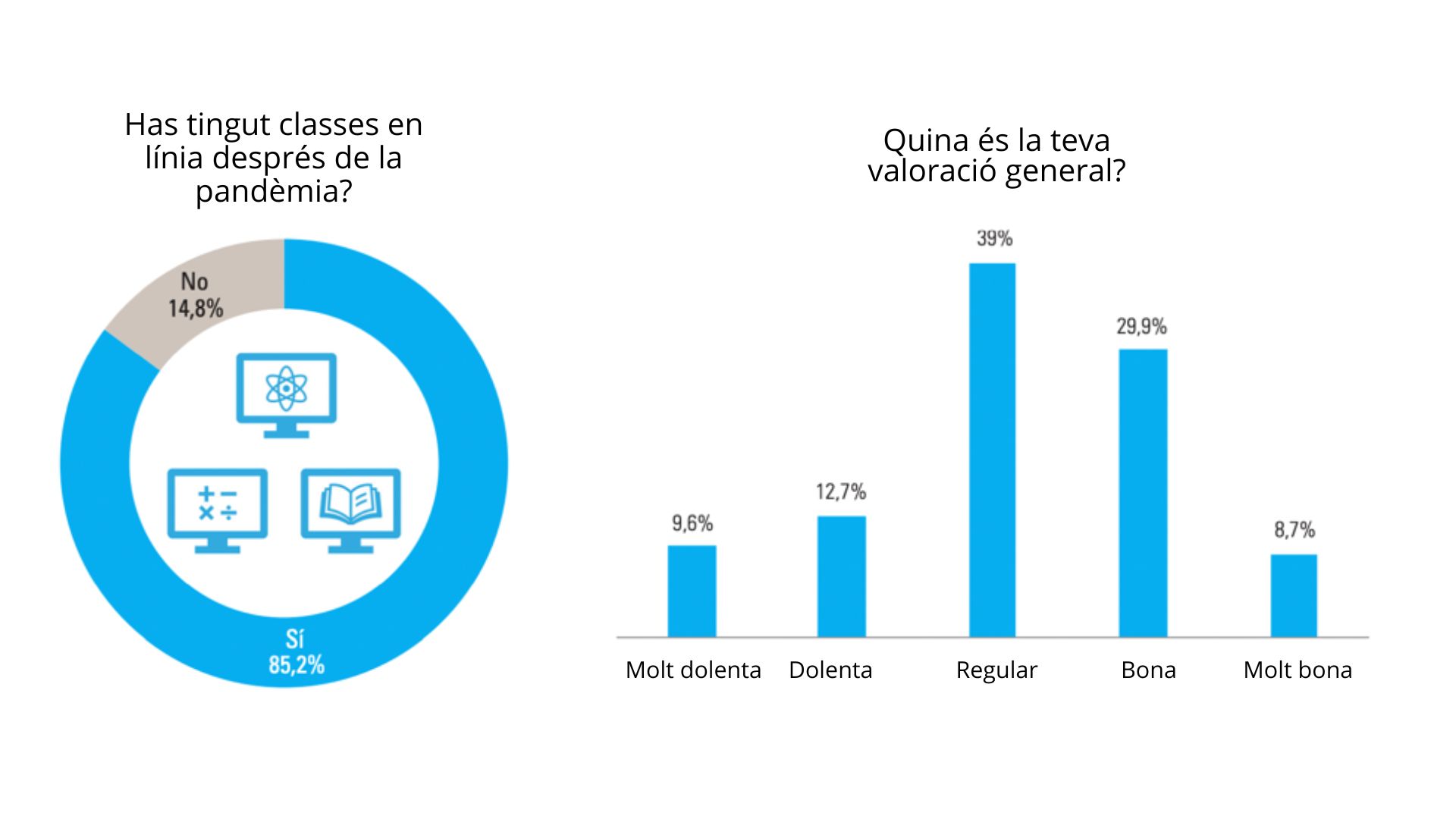

According to a study conducted on more than 50,000 adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years in compulsory secondary education, there is huge room for improvement in digital education, a field in which more than 70% of students have felt burdened or overwhelmed by their study load, having difficulty organising themselves and suitably dealing with all tasks required of them. Fewer than half of the adolescents surveyed believe it has been a good way of learning. Moreover, one in every four students states that they have had a poor or very poor experience, with most reporting not a very good experience. Indeed, this is without even considering the challenges teachers face. In view of this evidence, it is worth stopping to re-assess the digitalisation of education and understand who it truly benefits.

Related: We invite you to form part of the Education Opportunities Laboratory we are setting up!

Source: Andrade, B., Guadix, I., Rial, A. and Suárez, F. (2021). Impact of technology on adolescents. Relationships, risks and opportunities. Madrid: UNICEF Spain

Children are not products

Just as the quality of browsing and the type of content seen are relevant, in order to benefit from a healthy digital experience privacy and security are relevant as well. In this respect, the industry has an undeniable responsibility in providing secure digital services suited to the age of the users. Probably owing to the urgency with which digital learning infrastructure had to be implemented, added to the lack of technical knowledge on the part of decision makers and an absence of criteria from public authorities, education has been digitalised without fully comprehending what doing so entailed or what we have left behind as a result.

Education has been digitalised without fully comprehending what doing so entailed or what we have left behind as a result.

Are we aware that some online education systems (EdTech) compile private information from children while they study at home? Human Rights Watch (HRW) has reviewed 164 education technology products in 49 countries and has come to the conclusion that 90% “risked or infringed on children’s rights”. Have any parents given consent to the digital activities of their children being monitored? Are parents aware of the digital rights of their offspring? Do the authorities know that identity, location, device and friend-related data have been compiled to be sold on to advertising companies? The lack of awareness is so widespread that almost every country has publicly backed products that breached the digital rights of children according to this report.

Education in a digital setting entails new risks that must be foreseen and minimised before the most susceptible members of our society are required to develop within these settings where they may end up becoming products. The ease with which data can be compiled, stored, processed and controlled in digital learning environments has led to a technological boom. Nevertheless, as indeed UNESCO acknowledges, this is a double-edged sword because on the one hand it offers huge potential to provide personalised, enhanced learning that is not fixed to a specific location, but on the other it can lead to an undesirable concentration of power, raising the risk of the data being used to the detriment of students. Consequently, it is necessary to strike a balance between using technology to progress in transforming education and safeguarding individual rights and privacy.

It is necessary to strike a balance between using technology to progress in transforming education and safeguarding individual rights and privacy.

As providers of tele-education platforms, the tech giants tend to apply specific internal policies that restrict advertisements aimed at children and adolescents, but it is not enough to leave such a relevant societal issue down to the whims of the private sector. The risk is not only that maps of relationships or behaviour will be plotted out while children are taking part in these remote classes, but also these platforms seemingly install trackers that monitor the children over the Internet outside class hours, after they have left their remote classroom, and go on to design advertisements based on their behaviour.

Some initiatives that should be followed

Fortunately, unlike algorithms we humans are excellent at coming up with creative solutions. Several initiatives have been under development for some time in various countries which could provide inspiration.

- Common Sense is one of the main sources of technological advice in the USA. Millions of parents and teachers trust the comments and advice it gives when browsing in the digital world with their children. One of its most successful programmes assesses educational technology products and applications so that parents and teachers can choose which one to use with their children based on this knowledge.

- Webwise has developed a policy generator that can be used by all schools. This free tool allows schools to create their own personalised policy and decide on a series of agreements that must be signed by all parties involved. These agreements relate to how and for what the technology will be used according to the needs of each school.

- The Student Data Privacy project was set up to organise parents as regards the permit for education technology providers to collect data and metadata in schools.

- Australia has created the eSafety Toolkit for schools incorporating various explanatory modules about what needs to be known in order to create more secure digital settings.

- Greece, Norway and Switzerland have launched programmes with a single, secure login for schoolchildren.

- In Belgium, Ireland, Latvia and Luxemburg schools receive guidelines about how to effectively protect students’ privacy.

- In France and the USA, national laws have been enacted to protect students’ data.

- In the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Nova Scotia, data protection is governed by provincial policies that guide schools to allow them to operate within local legal frameworks.

It appears obvious that there is much to do in this area and that a balance needs to be found urgently between progress in digitalisation of education and the safeguarding of children’s digital rights.

Related: Algorithms under scrutiny: Why use AI in education?

Where do we go from here?

Ever since the pandemic forced everything to move online, new situations have become established which need to be reviewed, although this time with no rush and from a critical perspective. The experience of the past few years enables us to truly compare whether online learning is the panacea that was heralded or if it will need to develop. Technology unquestionably forms part of the education of the future, although an agreement has yet to be reached about who should provide it, how, to what extent and why.

Technology unquestionably forms part of the education of the future, although an agreement has yet to be reached about who should provide it, how, to what extent and why.

Young people already make widespread use of digital tools from a very early age, not only in their personal lives but also at school. Lack of control over what platforms do with their data is genuine and, what is more, in the field of education there do not appear to be specific or even standardised criteria for determining which digital service providers children will use. Tackling a challenge on this scale involves understanding the urgency of the fact that every single day millions of children are exposed to the collection of their information by these platforms. There is no single solution, or even an easy one, but we have set out five proposals on where to begin:

- Strengthening the independence of children through knowledge, highlighting the importance of data and how to protect them.

- Providing complaint mechanisms to ensure rights can be truly exercised.

- Forming a coherent approach that supports all education systems in each local area with effective practices and clearly defined elements which set out forms of action.

- Training teachers on digital rights and cyber risks.

- Setting up external auditing mechanisms to verify that the platforms are adhering to regulations.

There is an increasing need for global approaches in common fields. In order to deliver this, cooperation and partnerships must be strengthened. When it comes to such a sensitive issue, the sharing of knowledge and the setting of regulations is fundamental and, indeed, these regulations should be as homogeneous as possible to encourage compliance.